Nina Simon giving an opening intro to Museum Camp 2014 at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History. Photo: David Shaw

I am grateful for the sleep-away camp experiences I had growing up. Camp helped me learn how to connect with strangers in a new and uncomfortable place, largely through shared rituals and challenges (from campfire songs to field days to bunk chores). I was able to try new activities in a supportive environment offering both an escape from everyday life and the safety of structure and routine.

Now, the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History (MAH) has been exploring the power of “camp” as not only a formative childhood experience but a powerful professional development tool. MAH’s Executive Director Nina Simon initially proposed “ditching conference experiences for camp experiences” in 2009, and brought this vision to fruition in summer 2013 with the MAH’s inaugural “Hack the Museum camp.” This program gave 75 diverse museum professionals 48 hours to design an unconventional exhibition for the MAH’s main gallery that was previewed to the public on the last day of camp. In 2014, the MAH partnered with NYC-based arts service organization Fractured Atlas to host a second camp for 100 professionals interested in “social impact evaluation” with Nina Simon and Fractured Atlas research director Ian David Moss as co-directors. During both summers, participants got an immersive, 24/7 live/work situation complete with group meals, planned activity periods from morning to midnight, and even the option to camp out in sleeping bags in the galleries and trek to shared showers at a local gym.

I was lucky to participate in both camps. Though I eschewed actually sleeping at the museum both summers, I found myself as fully engaged, inspired, and rejuvenated by this camp experience as I was when I first left New York City for four weeks at a Southern New Jersey farm-turned-arts-camp at age 12. Now that I’ve just completed my second Museum Camp, I’ve summarized my thoughts on what makes MAH’s specific camp model so effective (and thought-provoking):

Fostering learning through shared problem-solving

After Museum Camp year 1, Simon reflected, “It is amazing to actually DO things with colleagues in professional development situations instead of just talking.” Any youth development professional will tell you that hands-on learning is the most effective kind, but conferences I’ve attended as an adult have rarely offered participants the opportunity to create or research something with tangible outcomes. At museum camp both years, the group of geographically and professionally diverse participants was split into teams of 5 to do just that, with expert “camp counselors” acting more as facilitators than instructors.

Posts by Nina Simon, Paul Orselli and Maria Mortati all describe the 2013 camp groups’ endeavors to create “risky” exhibits from various museum objects. At “Social Impact Evaluation” camp this year, each group was assigned a site or program in Santa Cruz and developed a related research question, hypothesis, and data collection methods. We had to actually conduct this research out in the community and analyze the results in the span of approximately 24 hours. In many cases this evolved into the use of similar DIY, interactive and wacky tactics to our exhibit designs the previous year, consistent with the MAH brand of participation (for summaries of all the group’s projects, see http://camp.santacruzmah.org/ as well as James Heaton’s and Nina Simon’s reflections).

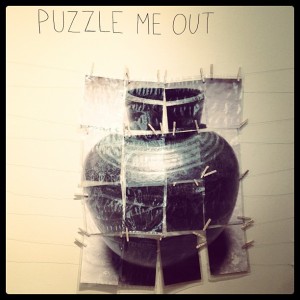

Both years, to achieve the daunting outcomes in the time allotted, we all had to actively teach ourselves and each other new things: In 2013 I figured out how to create an enlarged digitally printed puzzle of a ceramic vessel to help people look more closely at the object itself. This year my team had to employ heightened compromising and listening skills as we struggled to reach a workable hypothesis about our research site of Santa Cruz’s San Lorenzo Park. From my graphic designer teammate, I learned not to underestimate the value of old-fashioned poster paper charts and post-its for group brainstorming. I learned new ways of approaching people to take surveys through my community advocate teammate.

Interactive puzzle activity I designed for 2013 “Hack the Museum” exhibition, as part of my group’s overall exhibit designed to make people look more closely at a Bruce Anderson ceramic urn from the MAH collection.

Setting us up for success by setting us up for failure

Museum camp is built on the principle that we will be our most innovative when working under “absurdulous” constraints (to use a popular word from “Hack the Museum” camp) that would normally be seen as a recipe for failure at our jobs. In 2013’s camp, knowing that our exhibition would be presented to the public as an “experiment” freed us from having to stick to expected gallery conventions. This year we had permission to test out un-conventional data collection methods without worrying about whether the results would influence funders or organizational decisions–resulting in what Simon called “a small test tube of ideas and possibilities for opening up the way we do social impact research.”

I believe that my group this year in some ways “failed” in our research by relying too heavily on people’s self-reporting to determine how their memories of San Lorenzo park connected to their park use. The experience might have been better if we had been able to do a “test run” of the method and improve it at a final research session—most groups also reported that they could have benefited from this revision process.

Yet as a result of seeing what didn’t work as well in my group and others’, in future program evaluations, I will know how to design survey questions with less room for interpretation, and know when it’s best to use observations or in-depth interviews rather than surveys. I will probably experiment more in future evaluation work with engaging signage, props, and even participatory art activities, which is something I think my group and others did very well (one group did a “one minute art project” in lieu of a traditional survey; another handed people funky buttons and observed willingness to wear them as an indicator of their willingness to be “ambassadors” for downtown Santa Cruz). After my second year of camp especially, I am convinced that that in any type of work I can sometimes be more effective if I privilege constraints over thoroughness in my approach.

This 2014 Museum Camp team created a “one minute art project” in which people drew how they were feeling on stickers and placed the stickers to correspond how they had traveled to the Santa Cruz boardwalk that day. Image courtesy of the “One Minute Art Project” group

Using ritual and fun to re-connect with our own creativity

Team-building activities and organized breaks were important both years to work flow as well as shared culture. Daily “siestas,” morning yoga, spontaneous dancing, long walks to outdoor locations and even a beach swim in 2014 kept us refreshed and satiated our desire to network with a diversity of individuals outside our work groups.

I have also found as a curator of participatory art that encouraging adults to act like kids helps spark the type of creative risk-taking associated with a time in our lives when we were less afraid of judgment and failure. At Museum Camp, we were served hot chocolate or college cafeteria-style cereal buffets, and invited into a “confessional tent” reminiscent of middle school slumber parties. In 2014, a rollicking karaoke night ended with a group sing-along to “We Are the Champions” which was repeated to close out the last day of camp in true summer camp huddle fashion.

I found the overall experience in 2014 less work-intensive and more social, with three rather than two days to complete the assignment and a less concrete deliverable—an online reflection and photos as opposed to something on view in a public gallery. Though in some ways I missed the faster-paced, higher-stakes feel of 2013, I appreciated the active learning that still took place during the “fun” breaks, such as the conversation I had with a camper from a different group about how we’ve approached curating contemporary art for children.

My experiences at both camps support Nina’s hypothesis that there’s something truly valuable about networking with diverse, talented professionals in the context of shared problem-solving interspersed with organized fun. Some questions still remain in my mind, however:

How can we best define key terms?

In her reflection on the first camp, Simon admits that “everyone’s definition of risk is different,” and this caused some confusion especially among non-museum professionals in how to approach designing a “risky” exhibit. In 2014, the term “social impact” proved easier to research at some of the groups’ sites that at others. Certain local programs had clear missions for impacting participants that easily informed a research hypothesis (i.e. that First Fridays at the MAH encourage interactions between strangers) while unstructured public spaces (like San Lorenzo Park) did not. I’m also not sure that all groups’ research questions actually related to impact, as opposed to short-term behavioral change or existing attitudes.

When do program evaluation activities interfere with evaluating typical behaviors in a space—and when does evaluation become another form of programming, or marketing? (a hat-passing activity performed by one of the groups in the museum, for example, was a social intervention in itself in addition to a tool for measuring strangers’ interactions). Simon points out that while “every active research method is an intervention,” many of the groups’ interventions “yielded really interesting information that was not visible in more passive research methods.”

How can we balance small group experiential learning with traditional “conference style” instruction and reflection on best practices?

Each camp began with hands-on workshops by counselors on key methodologies that informed how we approached our assignments, and in my case future work in the field. The exhibit I curated right after camp last year incorporated concrete suggestions from Nina’s “effective prompts for exhibition participation” workshop (in addition to an overall “riskier” approach inspired by camp). Though it would have been hard to take any more time away from the group work, I would have liked to not have to choose between all the different workshops both years, or at least have access to full video recordings of the ones I missed. “Lightning talks” by fellow participants inspired us with real life examples of innovation, and given the wealth of experience all these presenters clearly had to share, it would have been nice to also build in time for Q&A with them.

How can we stay connected and inspired?

Camp Facebook and Twitter groups have been great tools to discuss both logistics and ideas before and after camp, and continue to share our individual work. Could there be more formal ways to continue to congregate around thought provoking questions or help each other solve problems that come up in our day jobs?

Where else can we set up camp??

If camp is the professional development format of the future, how can we make conferences, and even workplaces, more camp-like, whether we are designing exhibitions, running programs or evaluating this important work we do?

It’s great to see reflections from our only camper two years in a row!

The 2014 camp was almost entirely process-oriented, with a much less high-stakes product than last year. I realized watching 2014 teams that they were going through healthy struggle but not the frenzy that characterized some of last year (and in some cases, boiled over). The schedule was more relaxed and there was less concern about “getting it done,” which allowed people to learn more in the process. Still energetic, but not quite so frantic.

I’m not sure that one is better than the other (creating an exhibition was awesome) but this year felt more sustainable to me as a format and schedule going forward.

LikeLike

Katherine this is a very insightful and informative post. The multiple takes we all have on the karma Hat project show that an inspired and simple idea can really get things going. This is clearly an intervention, but as aptly points out “Many of the most interventionist projects, like the Karma Hat, yielded really interesting information that was not visible in more passive research methods.” For me this is something worth thinking about.

LikeLike

Perceptive indeed — and in a world that seems t increasingly unwilling to communicate across the lines of our naturall-occuring groups, these are useful encouragements for other organizations that, as the author says, “connect strangers in a new and uncomfortable place, largely through shared rituals and challenges (from campfire songs to field days to bunk chores)…,” via trying “new activities in a supportive environment offering both an escape from everyday life and the safety of structure and routine.”

LikeLike

From my POV 1.0 was more of a sketch- a massive proof-of-concept for the overall idea of a museum camp for a spectrum of professionals. Really like the theme, projects and refinements this year. Great post, thank you for the write up!

LikeLike

Pingback: Facilitating Artistic Studying (for Professionals): Extra Notes on MuseumCamp | TiaMart Blog

Pingback: Facilitating Creative Learning (for Professionals): More Notes on MuseumCamp | archaeoINaction